Verde Valley Vineyards Get Serious About Sustainability

RED, WHITE AND GREEN

“Sustainability” is a buzzword so broadly applied that the meaning is sometimes unclear. The more favored term now used for earth-friendly agricultural practices is “regenerative.” Both terms embody a fundamental principle: to do no harm to the environment and to work in harmony with nature to protect the systems of nature that support life: clean water, clean air, healthy soil and flourishing, diverse ecosystems.

As Arizona’s wine industry grows, pioneering local vintners are forging paths towards sustainable viticulture and wine production. Wine industry organizations hope to showcase these sustainable aspects of wine production and establish wine grapes as a practical, climate-adapted crop for the future of Arizona agriculture.

In addition to the agricultural income, wine-related tourism has provided needed economic growth to rural areas and boosts tourist-related economies in the hotel, restaurant and tour guide sectors. This is particularly true in the Verde Valley where tourism is a strong economic driver.

Verde Valley vineyards are small, and winemakers in this area strive for the best quality grapes, not quantity. They know good stewardship of the land they cultivate, and of their water resources, will yield superior grapes and robust long-term production.

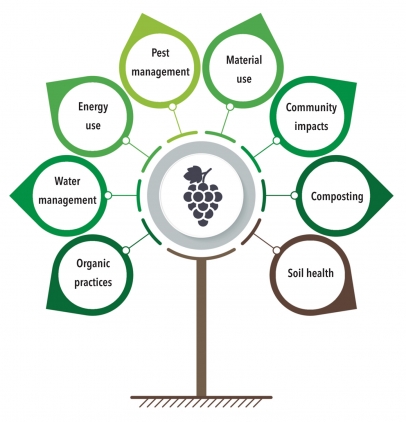

Sustainable grape growing has many components.

As the wine industry takes root in the Verde Valley, grape growers have been experimenting to discover what works in their vineyard habitats to address the usual current challenges of agriculture as well as future challenges brought on by climate change.

Certified Organic grape growing prohibits the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides or poisons. Although none of these wineries is Certified Organic, these Verde Valley grape growers do as much as possible to achieve organic standards because they believe that over time chemically treated soils become degraded. Poor soil weakens the vines and yields grapes of inferior quality.

Reasons for not pursuing the certification vary. For some of the smaller vineyards, organic certification is expensive. For others such as Page Springs Cellars, manager Luke Bernard tells me, the occasional need to protect a crop from a radical fungal infestation requires chemical measures, even if it is only copper sulfate, a natural organic compound, which nonetheless fails certified-organic standards.

Organic certification is only one spoke in the wheel of sustainable practices. Others are shown on the graphic above.

We interviewed four wine producers in the Verde Valley region who are listed on the Sustainability Alliance website for Sedona and the Verde Valley and talked with them about their growing practices and sustainability:

Sustainability Alliance Verde Valley Wineries

Page Springs Cellars

1500 Page Springs Rd., Cornville

pagespringscellars.com

Clear Creek Vineyard and Winery

4053 E. Highway 260, Camp Verde

clearcreekwineryaz.com

Salt Mine Wine

536 W. Salt Mine Rd., Camp Verde

saltminewine.com

Southwest Wine Center

601 Black Hills Dr., Clarkdale

southwestwinecenter.com

Water is key.

Wine grapes are a drought-tolerant specialty crop requiring less water than cows, cotton, corn or alfalfa. Vineyards also yield a higher economic return per acre of land and acre-foot of water than these crops. Instead of the traditional flood irrigation used on feed crops, most grape producers are installing drip systems. Chip Norton of Salt Mine Wine in Camp Verde says his grapes use half the water traditional feed crops would need.

Page Springs Cellars (PSC), which has a very busy tasting room and bistro, is “net zero” in water use, according to Luke Bernard.

Most of their water comes from artesian springs, so to ensure the future viability of the aquifer PSC has built a municipal-grade effluent treatment facility for aquifer recharge. They are still testing this, but as an added purification measure they have installed a wetland filtration system that uses plants to further purify the treated water.

Additionally, PSC has signed on to an innovative collaboration called Verde River Exchange, where private landowners who maintain river water rights are paid not to use it, offsetting the use by the PSC vineyard. This is a significant contribution to the greater hydrological environment of the Oak Creek watershed, which PSC shares with its neighbors.

Ignacio Mesa, owner and vintner at Clear Creek Vineyard and Winery in Camp Verde, has built a large pond to store irrigation water. With a complex system of valves and gravity-fed lines he avoids using electric power to pump water. Five species of fish inhabit the pond, their manure contributing to the fertilization of the vines.

Clear Creek Winery and Salt Mine Wine both practice no-till agriculture to keep moisture in the soil to reduce irrigation needs.

“For my established 3-year-old vines I water deeply every three weeks. This uses less water over time and ensures deep roots. Deep roots withstand dry periods and access many nutrients to produce quality grapes,” Mesa says.

In collaboration with the city of Cottonwood, the Southwest Wine Center is using A+ reclaimed effluent for irrigation, a model of future water use across the state.

Pests can be controlled without decimating the eco-system.

Grapes are food for many creatures, including birds, bugs, raccoons, rodents and skunks.

To help control insect predation at Salt Mine Wine they weed and mow as needed between rows instead of using pesticides and herbicides to control harmful insects. This widely used organic method also allows pollinators and other helpful insects to thrive in a balanced ecosystem.

At Clear Creek Winery, Mesa erects cloth net tents over the vines, keeping out June bugs and birds. He also uses geese and chickens for insect control. While the geese will eat weeds and bugs, they also like grapes so he has to train the vines high enough that the geese can’t jump up and pluck the clusters.

“If a goose is thin, it can jump high enough to eat the fruit, so I clip one wing. If the goose continues to jump and eat grapes, I clip the other wing. If clipping both wings doesn’t stop it from jumping, I put it in the oven,” he tells me. “I try to raise fat geese and fat chicken breeds so they won’t jump or fly.”

But fowl attract other predators such as coyotes, raccoons, foxes and skunks. To deter them Mesa has two large Bernese Mountain Dogs. They have two layers of fur and need to be clipped for comfort in the summer heat, but they are active at night when the predators come out. He still has to trap the skunks, however, so the dogs won’t get sprayed. It may be colorful, but the integrated pest management system is far more complex than conventional pest control.

Page Springs Cellars has been careful to leave a wildlife corridor through the vineyard to the creek so animals can access the water. They use solar powered loudspeakers that play recorded predator birdcalls to scare off grape-loving wildlife. The y also use live traps for some predators.

Soil health is essential for strong, healthy vines and good fruit.

Achieving healthy soil requires nurturing the complex living system where water, cellular organisms, decaying plant matter, mycorrhizae, worms and other creatures interact to create a vital, regenerative environment for plant life.

In addition to the fishmeal fertilizer produced by his pond, Mesa plants nitrogen-fixing cover crops including winter peas, rye grass, clover or vetch to keep the soil healthy and productive. He also composts his pomace.

The Norton brothers at Salt Mine are still in their start-up phase, and like many growers currently use nitrogen fed through the drip irrigation, or “nutrigation.”

PSC incorporates grasses and other plants between rows to retain healthy levels of soil nitrogen.

Energy efficiency is achievable.

Southwest Wine Center (SWC) is a hands-on teaching facility with a state-of-the-art winemaking facility, 12-acre working vineyard, wine business curriculum and tasting room. In 2019 it received the governor’s Arizona Forward Award of Distinction for Innovation.

Tasting Room manager Lisa Russell says the recognition honors the vision of SWC’s founders for the adaptive reuse of an old racquetball court. Outfitted with rainwater harvesting and recycling capacity and incorporating passive solar energy and maximum daylight for operations, it is LEED certified. Lisa hopes that one day they will have the funds to install a full solar array.

Also at the forefront in green energy efficiency, Page Springs Cellars has an extensive solar array that supplies 75—85% of their power for the full operation in Page Springs. The array of panels also serves as shade for parked cars. They have another 10-acre vineyard in southeastern Arizona that is 100% solar powered.

Composting can be a challenge.

It might seem to be an obvious regenerative practice for a farm, but composting can be a challenge for some vineyards that do not have space to manage the large volume of pomace, the residue produced from pressing grapes.

Another challenge of pomace is that it must be removed quickly, before mold and fungi develop and fruit flies infest and lay eggs in it. Cattlemen can feed it to their cows, but it must be collected right away, so timing is tricky. At SWC and PSC most of the pomace is by necessity delivered to the municipal landfill.

At Clear Creek there is room for composting. After the pressing, the pomace is mounded and covered in dirt for two years before being used for fertilizer.

At Salt Mine, the pomace volume is still low enough that it can be spread thinly over the fields where it dries out and serves as mulch.

In a creative twist, Page Springs Cellars makes body butter from a portion of their pomace, which they use for massage treatments in their spa and sell in the shop. Pomace, Bernard tells me, can also be dehydrated and ground into flour for cookies, breads and pastries.

A pomace collection service and value-added product development could be potential business opportunities for the future.

Material reuse and recycling can reduce waste.

Another sustainable innovation being considered by some wineries is using kegs with taps instead of individual bottles for tasting rooms and restaurant clients.

Some wineries donate their used bottles to non-commercial and small wine makers, who wash and use them to bottle their own wine.

Some artisans use the bottles to create cheese plates, trivets or spoon rests. Used bottles can be used to build attractive glass walls or room dividers.

Vine trimmings from winter pruning also require space for disposal, or some means of reuse or recycling. Some artists collect the vines from the vineyards to make wreaths or baskets or other decorative items. Dried vines can also be chipped for mulch.

Used oak barrels can be transformed into benches and other furniture, wall treatments or artwork. PSC uses individual staves from used barrels to “oak” wines in their stainless steel tanks.

Looking to the future.

At this point in the nascent Verde Valley wine industry, sustainable practices are a matter of philosophy and lifestyle choice, and still subject to experimentation rather than an industry standard. But this could change.

According to Michael Pierce of Southwest Wine Center and Bodega Pierce Winery, “Implementing practices from organizations like California Sustainable Winegrowers Alliance will be a starting point in creating a framework for sustainable viticulture in the state. The Southwest Wine Center at Yavapai College has committed itself to develop best practices for limiting our impact on the environment. Showcasing a variety of vineyard management approaches and the natural inputs required is a strong element in the academic curriculum.”

Luke Bernard, manager of PSC says, “We are proud of our eco-friendly and green philosophy and values, shared by all the staff who work here.” Not surprisingly, Eric Glomski, founder and owner of the winery is a former professor of ecology.

By researching, experimenting, documenting and perfecting the best regenerative grape growing and management practices, Arizona winemakers are helping to define sustainable viniculture and viticulture for current and future wineries across the arid Southwest.

For More Information:

Arizona Vignerons Alliance

arizonavigneronsalliance.org

This group collects and shares individual producers’ data related to grape growing, yields, weather patterns and more to create a research database for the Arizona wine industry.

Sustainability Alliance

sustainabilityallianceaz.org

The Sustainability Alliance of Sedona has launched a business self-certification program with different bronze, silver and gold levels of recognition, so that members can incrementally improve their ratings. As a marketing tool this branding identifies them to likeminded customers who come to enjoy the experience of Sedona, and who subscribe to an environmentally friendly ethos.

California Sustainable Winegrowers Alliance

sustainablewinegrowers.org

The CSWA was founded in 2003 “to promote vineyard and winery practices that are sensitive to the environment, responsive to the needs and interests of society at large, benefit high quality grapes and wine, and are economically feasible to implement and maintain.”